When design meets the computerized stonemason

May 27, 2013

A few contemporary masters investigated these materials in the nineteen sixties, seventies and eighties, making products that combined high aesthetic qualities with great creativity. But these efforts, more than a vocation, seemed to be approaches tied to brief and circumscribed, although for some not episodic, opportunities. It was as though strong barriers rose up to limit the expansion of this area of research. So strong that even extremely creative and professionally capable artists were discouraged from going forward and were ‘sidetracked’ towards more performing materials.

Structural and contextual conditions undoubtedly bore down on this. The stone processing sector had little or no desire, independent from the economic and technological levels reached by individual firms, to be involved in the Italian design world, even though Italian design had been enjoying fortunate and almost unchallenged success on international markets ever since in the nineteen sixties.

For decades the stone processing sector, having closed the books on its rich pre-modern crafting traditions and their systems for transmitting know-how, strove to exclusively cultivate a market dedicated to flat stone surfaces, whether horizontal or vertical, finished or rough but in all cases always two-dimensional and lacking any added value other than that of being stone: a material that was thought to contain ‘in itself’ the characteristics of luxury and value that the building market had assigned to it.

And we also have a certain prohibitionism, backed by ethic motives, that dampened the desires of architects and designers to overcome this concept of stone as being able to do it ‘in itself’, resisting going beyond the simple sawn slab, squared and standardized in a few basic formats. And so we have had to wait several decades before the research efforts of past masters, interrupted, found a new burst of energy that permitted this ‘going beyond’: on the one hand the market developed computerized numerical control machines with specific applications for stone materials, leading the majority of companies to equip themselves with these new processing tools; on the other hand architects began working on computerized drawing tables with sophisticated three-dimensional modeling programs, opening up new prospects for stone projects. What made these new discoveries even more fertile, permitting their creative use, was the possibility of connecting digital three-dimensional projects with these new processing machines, creating an extremely efficient circuit between conception and finished object.

Stone, in this extraordinary perspective, began being seen and investigated from a different standpoint. The design area, in particular, became keenly aware of the new creative potential for actions using the latest generation of software. It was able to simultaneously envision the possibility of transferring ancient handcrafting capacities to these machines and, at the same time, of having industrial processes that replicate, serially and at extraordinary speeds, even highly complex formal objects.

This has opened up a new reality for stone activities, defined as that of the ‘computerized stonemason’, a phase when even stone products – which once required special manual crafting expertise to be made – could now be efficiently inserted into totally robotized production processes. This has been an area of study for over a decade by the school of Claudio D’Amato at the University of Bari, searching for stereotomic building components starting from classic architectural codes.

Raffaello Galiotto’s stone path takes its beginnings from this context.

Galiotto, backed by solid experience in the world of industrial design, precociously saw the advantages of transferring the methodological and technological know-how furnished by this discipline to stone materials. And this was not merely a question of expanding the use of computerized machines to a much larger and more open sector of services compared to the extremely limited use normally practiced in processing plants. Rather, and above all, it was a question of investigating the latent potential of stone materials in the precision processing world of these machines themselves.

Quite different results, in fact, can come from in-depth engraving of the same pattern on stone or marble with different petrographic compositions. Fidelity of execution, on some lithotypes, is extremely close to the original project in terms of texture and calligraphic precision. On other types the margins for imprecision can generate uncontrolled effects that alter the meaning of the work. In yet other cases these eventual undesired alterations may give unforeseen tactile qualities to the stone surface. These same concepts apply to the machines as well: they are still instruments in development phases that can offer – by changing the tools that are used – extremely different effects. In the end the ‘computerized stonemason’ begins to act like his manual ancestor.

Designers, through this interaction of new techniques and new know-how, increasingly take direct control over all the operations required to make a product.

But it remains clear, however, that final formal results are not achieved on the drawing table: they need an accumulation of in-the-field technical and creative experience, something that begs for creation of a new intellectual discipline.

This is the direction taken by Raffaello Galiotto in his last five years as designer. A fundamental factor in his journey has been his roots in a stone production zone, the Chiampo Valley, which has both the ancient handcrafting traditions of this sector and also a substantial number of entrepreneurs who have reacted to the recent economic crisis by investing in innovation and research.

Galiotto’s first experience in stone modeling involved a consortium of business in the Chiampo Valley and had, as its theme, a rethinking of Veneto’s great culture of the past. He then takes a cue from this and goes on to unfold an extremely efficient communication strategy on the new potential offered by digital design integrated with numerical control machines.

His two exhibitions, ‘Palladio e il design litico’ in 2008 and ‘I Marmi del Doge’ in 2009 are aimed, firstly, at the stone processors themselves, who can concretely experiment with a new and unexpected technology for transforming their products. And, secondly, the exhibitions present high quality objects that permit businesses to present themselves to the international market with absolutely innovative and novel catalogues which are, at the same time, inspired by the prestigious classic culture of the Veneto territory. All of which becomes an operation of innovation and marketing that creates a solid base for the increasingly pregnant research path taken by its author.

The exuberant creativity of Raffaello Galiotto, starting from these experiences, spreads out in many directions, experimenting with individual businesses, including, in particular, Lithos Design, cycles of works and products which meld art, design and architecture.

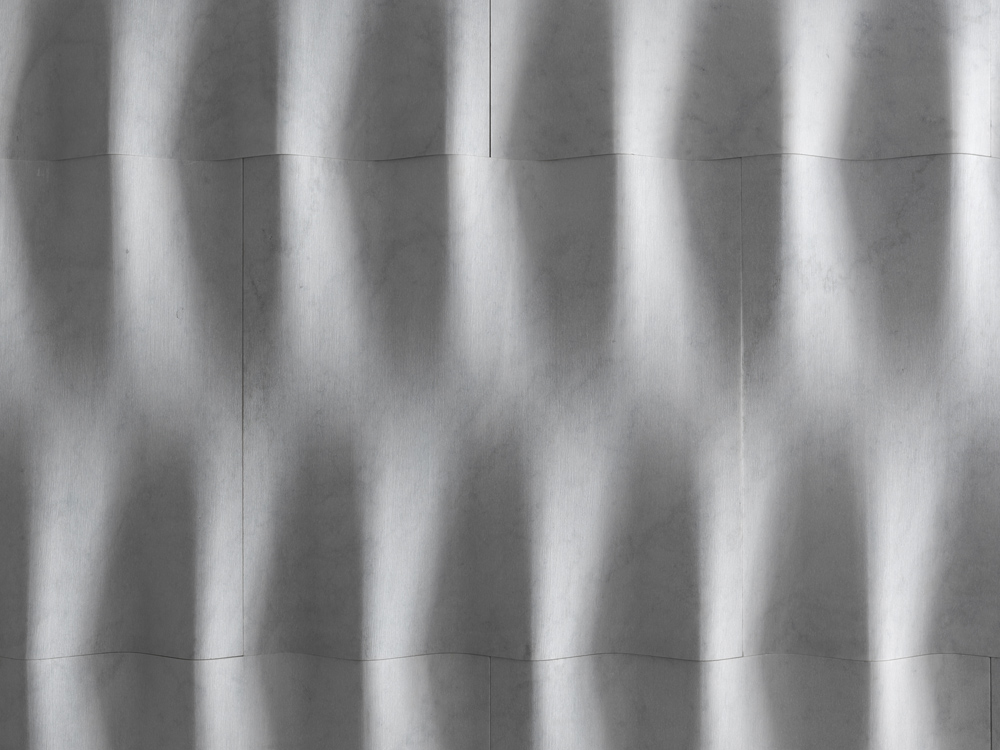

The exhibition ‘Luce e Materia’ (Marmomacc, 2011) and the collections made with Lithos Design ‘Le Pietre Incise’, ‘Luxury’, ‘Muri di Pietra’ and, most recently, ‘Drappi di Pietra’, are a series of steps forward in a wide ranging program of themes: modular wall coverings, three-dimensionality, lightness and intangibility, translucence, mirror reflection, stereotomic massiveness. Their declination, through different stone materials, indicates the starting points of many paths for exploration, investigation and continuation. One of the most fascinating of these themes is the change of scale of objects: the crucial passage from “the architecture of littleness to the architectural dimension” that all designers come to, sooner or later, and that Galiotto himself seems now to be preparing himself to confront.

back to top print

Post-it

ISSN 2239-6063

edited by

Alfonso Acocella

redazione materialdesign@unife.it