Stone design.

Research and products in two exhibitions from the 1980s

February 11, 2013

Gae Aulenti, detail of Jumbo, a table in marble produced by Knoll, 1964

The history of Italian stone design is complex and multifaceted; it has never been recalled in an structured way so far, even if it moved from Modern age into Contemporaneity being appreciated for the richness of its works and authors as well as for its peculiar and somehow dissimilar aspects.

Intriguing industrial experimentations on stone between the 1960s and the 1980s flowed into the 1990s minimalism and, at the beginning of the 3rd millennium, gave this material multiple characterizations both in projects and in products, and a balance of all this is yet to be written.

This essay concentrates on two exhibitions linked to two different moments of research and debate that are essential to understand the current scenario of stone design.

“Marmo Tecniche e Cultura”, Milan, 1983.

Debate and research among art, architecture and design

“Marmo Tecniche e Cultura” (Marble, Techniques and Culture) was organized by Giuliana Gramigna, Sergio Mazza, and Pier Carlo Santini and took place at the Arengario Palace, Milan, in December 1983.

This event, crucial for the developing of Italian stone design in the last decades of the 20th century, intended to catch the attention of the public on the different qualities of stones and marbles and on their cultural meanings; curators presented a series of works in the different domains of sculpture, architecture and – above all – product design, offering several types of technical experimentation and of functional and aesthetical themes. The main object was to further stimulate debate and research about possible productive evolutions of stone materials.

Franco Albini and Franca Helg, project for the marble flooring of Ritrovo Sportivi Shell in Valletta Cambiaso, Genova, 1954-61.

The exhibition and, consequently, its catalogue were developed starting from the analysis of the works by artists such as Guerrini, Noguchi, and Adam, who lived a strong and close relationship to stone materials; sculptures by Pietro Cascella, Gigi Guadagnucci, Francesco Somaini, and Giò Pomodoro were also described, all of these being created between the ‘70s and the ‘80s and representing different approaches, in expression and method, to stone and marble.

The section devoted to architecture presented stone buildings from the ‘30s by Giovanni Muzio and Giuseppe Terragni, and then works by BBPR, Gardella, Albini, Zanuso, and Carlo Scarpa, built between the end of the Second World War and the early ‘80s.

Sculptures and architectures were illustrated underlining the peculiar relationship between designers and machines, between materials and serial handcrafting or industrial production; this analysis depicted different levels of interaction that have been useful to study the phenomena of stone design to this day.1

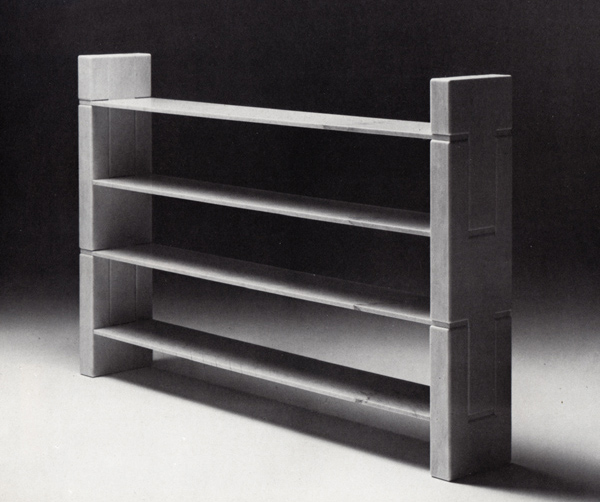

Renato Polidori, Biblos bookcase in marble, produced by Fucina for Skipper, 1976

The main part of the exhibition was devoted to design and conceptually valorised experimentations from the ‘60s, interpreted as starting point of an essential theoretical and critical debate on the possibility of renovating objects and furniture in stone; these experiences had relevant consequences on the production of the ‘70s and the ‘80s with stone items manufactured by the most important producers in the Italian interior design, as Knoll, Cassina, B&B, and Danese and with collections by brands exclusively dedicated to stone design as Skipper, Up&Up, Casigliani, Ultima Edizione, and Primapietra.

Piero Carlo Santini described this phenomenon in the catalogue essay about design, underlining the central role of the cultural and operative experience of Officina, born in Pietrasanta but developed in an International scale, in which different personal stories converged: that of Erminio Cidonio, head throughout the ‘60s of the Tuscan seat of Henraux, a multinational company in the stone domain, and those of artists, designers, art gallery managers and tenacious art critics as Salvini himself.

Cidonio, guru of a short but intense season that fused experimental projecting and entrepreneurship, invited in the Officina workshop people representative of each creative technique, who worked in absolute freedom using complex and unusual processes in order to renovate and re-qualify the marble object. The result of this activity was Forme 67, a group exhibition held in Pietrasanta in 1967.

Giulio Lazzotti, Peanuts wares in Bardiglio Imperiale marble and polished slate, produced by Casigliani, 1981

See Peanuts dishes from the Moma collection in New York

In the context defined by Officina experimentations, several individual projecting paths began, some of them more fruitful than others but in general of fundamental value, above all the experiences of Enzo Mari and Angelo Mangiarotti, but also the ones of Mario Bellini, the Castiglioni brothers, Gae Aulenti, and Tobia Scarpa: they obtained impressive results in formal and technological innovation of the stone product becoming a methodological point of reference still effective for current and future researches.2

1983 “Marmo Tecniche e Cultura” comprehensively recounted these articulated projects and productions exhibiting the Paros vases by Enzo Mari for Danese; the bowls and boxes in marble by Angelo Mangiarotti for Horus (Skipper), as well as the considerable collection of alabaster items for Horus, Conexport and Società Cooperativa Artieri Alabastro by the same author.

Sergio Asti’s vases and holders in marble for Up &Up and Knoll were exhibited as well, together with the marble ashtrays by Gianfranco Frattini for Henraux; the wares in alabaster and Bardiglio marble by Giulio Lazzotti for Casigliani; and the alabaster objects of the Batu collection by Enzo Mari for Danese.

Angelo Mangiarotti, vase in Volterra alabaster, produced by Conexport, 1983

Next to every-day objects, lots of furnishing items were present as well: the Biagio lamp by Tobia Scarpa for Flos; the Eros and Incas tables by Mangiarotti for Fucina (Skipper); the Samo and Delfi tables by Carlo Scarpa and Marcel Breuer for Simon International; the Jumbo table by Gae Aulenti for Knoll.

And then the Colonnato table for Cassina and the Grande Muraglia sofa for B&B Italia, both by Mario Bellini; the Biblos shelf by Renato Polidori for Fucina; the Mega tables by Enrico Baleri for Knoll; the Metafora table by Lella and Massimo Vignelli for Casigliani.

The exhibition showed in addition the Rotor 4 table by Carlo Venosta and the Unipede tea-table by Giulio Lazzotti, both for Mageia; the Buñuel dressing table for De Padova; the I Menhir small tables by Lodovico Acerbis and Giotto Stoppino for Acerbis International; and the Waiting System seats by Tecno.

Lodovico Acerbis and Giotto Stoppino, I Menhir tables with compound bases in marble and surface in crystal, produced by Acerbis International, 1983

These design elements were obtained with advanced techniques in cutting, milling, turning, mortising, and inlaying in order to valorise structural and expressional qualities of the different stone varieties. Object typologies and morphologies were numerous. The diversified scenario described by the exhibition outlined with effectiveness, in the curators’ words, “a brand new marble culture”, projected into modernity and in search of a “productive Humanism” other than

the flattening standardization occasioned by the uncompromising cost-production-technology mechanism. In this way stone became an essential material to create a bond between handcrafting and industry, based on process efficiency, product quality and proper solutions to the “problem of answering with this material to the needs of contemporary languages”.3

Disegnare il Marmo, Carrara, 1986.

Projects and prototypes for home design

From 28th May to 2nd June, 1986 the city of Carrara hosted the exhibition “Disegnare il Marmo. L’abitare” (Designing Marble. Home living), organized by Internazionale Marmi and Macchine di Carrara in collaboration with the local Accademia delle Belle Arti and ADI (Italian Design Association). The initiative wanted to promote projecting and productive activities focused on furnishing elements and building components made of stone, in order to stimulate an industrial production with high quality standards.

This event offered the occasion to create and refine projects and prototypes of stone elements linked to new functions and technologies: specific sections of the exhibition were devoted to home furnishing, to bathrooms, to kitchens, to terraces and gardens, to construction elements. Designers as Angelo Mangiarotti, Aldo Pisani, Egidio Di Rosa, Pier Alessandro Giusti, De Pas-D’Urbino-Lomazzi, and Pier Luigi Spadolini participated in the exhibition, showing a direct link to the productive realities of the Versilian city.

Egidio Di Rosa, Pier Alessandro Giusti, graphic studies for stone fountains, Carrara, Disegnare il marmo exhibition, 1986

Mangiarotti presented his Asolo table, in which he continued his research on gravity joints already begun in the ‘70s with the Eros and Incas table collections for Skipper; in his report of the project he wrote: “I believe the meaning of such an initiative as Internazionale Marmi and Macchine di Carrara is to be found in the projecting of an unconventional object, out of the production by other competitors in this domain, exploiting at their best the possibilities of the material and the technologies to manipulate it.

The suggested project is the result of studies on the material – in this case granite – and on the possibilities offered by its liminal performances”4. Its name derived from the “a solo” definition, stressing the exceptionality of a project in which the large stone surface was based not on strong truncated cones or pyramids as it had always been, but on plates with the shape of a trapezoid, in a delicate balanced system created according to the deep knowledge of physical and structural qualities of the material and to a correct technological application.5

Angelo Mangiarotti, Eros tables, produced by Brambilla (then Skipper, Cappellini, Agape), since 1971

See Eros tables in the collection of Triennale Museum in Milan

Angelo Mangiarotti, Asolo table, produced by Skipper (then Agape), since 1980

Aldo Pisani as well worked on the theme of putting thin elements together and exhibited a table with a central base compounded by seven stone plates, a translucent lamp originally studied for Venini and some wooden furnishing elements for the bathroom with marble veneers.

Egidio Di Rosa and Pier Alessandro Giusti, since 1984 art directors of Up & Up, a stone design brand, after collaborating in the production of Memphis, went further on their research; they worked on the production of sculpture-like elements as fountains, pools and seats, obtained excavating blocks with a machine especially developed by Officine Meccaniche Domenico Tongiani: it was a wire cutting machine for special conic moulding. So Di Rosa and Giusti reinterpreted traditional objects and furniture made of stone, almost entirely created by the handcrafting of artisanal gougers till then.

Aldo Pisani, project for a table made of marble plates, Carrara, Disegnare il marmo exhibition, 1986

The Carrara exhibition was a useful occasion for Jonathan De Pas, Donato D’Urbino, and Paolo Lomazzi to deepen their research on the theme of the fireplace: previously a mere decoration, it became an articulated functional and aesthetical element, able to establish a bond with surrounding space and users. In the ‘70s these three designers had already projected ceramic fireplaces where the volume of the fire holder was treated like a complex and highly three-dimensional shape, and in which the tiles designed the geometry of the composition.6

These designers created for “Disegnare il Marmo” a modular set of elementary solids made of multi-coloured stones that clients could variously customize. The base, the architrave and the mantelpiece were made of cubes, parallelepipeds and cylinders inspired by Freidrich Fröbel’s toys; its front was turned into a customizable yet serialized objet exactly as the prefabricated body of the fireplace.

Jonathan De Pas, Donato D’Urbino, Paolo Lomazzi, project for a collection of modular fireplaces made of stone, Carrara, Disegnare il marmo exhibition, 1986

The industrialization of the stone object, dominating the Carrara exhibition, was reaffirmed in Pierluigi Spadolini’s project as well. The architect used for marbles the systematic projecting logic and the research on aggregative modularity that characterized his work, conceiving an outdoor seat exhibited in the section about terraces and gardens. The standardized elements of the bench with rounded corners were enriched with special “significant” pieces to form a complex but flexible system that could generate areas and paths of various morphologies.

Pierluigi Spadolini, sketches for a modular outdoor seat made of marble, Carrara, Disegnare il marmo exhibition, 1986

From Mangiarotti to Pisani, from Rosa and Giusti to Spadolini, these projects at the exhibition in Carrara anticipated the development of the contemporary stone design, distinguishable by a technological conception of industrial nature yet fully integrated to an idea of customization of the product typical of limited handmade series.

The characters of this phenomenon, economically significant not because of its dimensions but for its qualitative values, had already been defined by Licisco Magagnato’s words in occasion of the third Mostra Nazionale del Marmo in 1968 and cited by Pier Carlo Santini in his introduction to the catalogue of the exhibitions in Milan and Carrara: “The contingent industrial design may not absorb more than the 5-10% of the marble production. But in this domain, we must say it again, only quality matters; the important thing is to give marble a new image, presenting it again to those who are forgetting this material as an element to work with. New forms obtained with industrial productive methods; suitable applications in adapt contexts. Designers’ answers […] seem to us particularly important because they trace a new path, a well-founded working method in the domains of school and handcrafting as well […]; there are more than 15,000 artisans in this sector […] and only in their workshops they can manufacture the products of the new Italian design, only there new machinery and working systems have been elaborated.”7

Carlo Scarpa, sketches from the project for Maser table, about 1970

The 1986 exhibition confirmed innovation and quality were the pillars of marble design, presenting the prototypes of tables made of stone designed by Marcel Breuer and Carlo Scarpa, the two masters who had collaborated in 1969 signing the Delfi stone table for Simon. In Carrara, thanks to the synergy between Simongavina - repository of the original sketches – and Henraux and Imeg companies, the refined projects for Breuer’s Fiesole table and Scarpa’s Maser table were fulfilled.

Chronologically located in the middle, between the first experiences with contemporary stone design by Officina and Forme 67, and the recent initiatives of Verona Marmomacc Meets Design to relaunch stone industrial design, “Disegnare il Marmo” was certainly, in 1986, a virtuous occasion in which a high-quality experimental workshop was created, mixing in a fruitful way designers’ vital creativity and the productive quality of marble industries.

by Davide Turrini

Notes

1 Both in recent history and in the current scenario, categories as artisanal replication, industrial serialization and multiplication of handmade objects are essential to analyze stone elements and working methods. For further details about this, see Guido Ballo, La mano e la macchina. Dalla serialità artigianale ai multipli, Milano, Jabik & Colophon, 1976, pp. 271.

2 About the Officina experience, Erminio Cidionio at the head of Henraux and the consequent development of Italian stone design from the mid-60s, see Anna Vittoria Laghi, “Cidonio, 1963-1965: cronaca di un’utopia” pp. 280-285 and Claudio Giumelli, “Pier Carlo Santini e il design del marmo” pp. 377-412, both in Anna Vittoria Laghi (ed.), Il primato della scultura. Il Novecento a Carrara e dintorni, catalogue of the 10th Biennale Internazionale Città di Carrara, Carrara, Artout, 2000, pp. 423; see also Lara Conte, “L’Henraux: i progetti, i protagonisti (1956-1972)” pp. 36-49, in Costantino Paolicchi, Manuela Della Ducata (eds.), Henraux dal 1821: progetto e materiali per un museo d’impresa, Pontedera, Bandecchi & Vivaldi, 2007, vol. II, pp. 87.

3 Pier Carlo Santini, “Il materiale marmo”, p. 23, in Marmo. Tecniche e cultura, exhibition catalogue, Milano, Promorama, 1983, pp. 103.

4 Angelo Mangiarotti, cited in Disegnare il marmo. L’abitare, exhibition catalogue, Pisa, Pacini, 1986, p. 28.

5 About Mangiarotti’s stone design see: Beppe Finessi, Su Mangiarotti. Architettura, design, scultura, Milano, Abitare Segesta, 2002, pp. 240; Beppe Finessi (ed.), Angelo Mangiarotti. Scolpire, costruire, exhibition catalogue, Mantova, Corraini, 2009, pp. 118; Francois Burckhardt, Angelo Mangiarotti. Opera completa, Milano, Motta, 2010, pp. 383.

6 Consider the interesting ceramic fireplace by De Pas-D’Urbino-Lomazzi published in Il vostro caminetto. Selezione di caminetti nell’arredamento rustico, moderno, in stile, Milano, Cavallotti, 1976, p. 108.

7 Licisco Magagnato, cited in Pier Carlo Santini, “Per un design del marmo”, p. 12, in Disegnare il marmo. L’abitare, op. cit. 1986, already in Momenti del marmo. Scritti per i duecento anni dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara, Roma, Bulzoni, 1969, p. 262.

back to top print

Post-it

ISSN 2239-6063

edited by

Alfonso Acocella

redazione materialdesign@unife.it